"The introduction of antibiotics into clinical use was arguably the greatest medical breakthrough of the 20th century"

You may have gone to the doctor recently and been prescribed antibiotics for an infection, but have you ever wondered about the history and process behind how the prescription came to be? That's exactly what Matthew Hutchings and colleagues explore in their paper Antibiotics: past, present, and future.

What are Microbes?

Microbes are tiny living things that you can only see with a microscope. Bacteria and fungi are two common types of microbes. When it comes to humans, bacteria have a dual nature. I like to say that they are our greatest allies, and also some of our greatest opps. We cannot live without them, but we are constantly defending ourselves from them.

These microbes form a community called the microbiome. Every human has a microbiome both inside and on their body, which is necessary for us to carry out a lot of processes, such as digesting food.

The next time you pass gas, don't be embarrassed. Instead, thank your gut bacteria for their hard work!

What are Antibiotics?

Antibiotics are medicines that may kill or stop the overgrowth of harmful microbes. Most antibiotics come from microbes themselves, and are called natural antibiotics.

To explain, I like to use the saying "You got too much dip on your chip." Imagine all these microbes as people that are hanging out together at a gathering. Everyone is just vibing, eating, and minding their business, but then one or a few people start getting too cocky or hogging the resources meant for everyone.

They start getting "too much dip on their chip," meaning overgrowing, taking too many resources, not uplifting others, and just trying to dominate the space. Well, the other microbes step in and are like, "Nah, you're doing too much!" so they release antibiotics or chemicals to "humble" them, which keeps the overconfident or harmful microbe from getting out of control.

Some microbes are always harmful (pathogens) while others are harmless, but then turn harmful depending on the conditions. Microbes in nature have been checking each other for millions of years using these natural antibiotics.

Humans noticed how microbes check each other and said, "Bet. We can use this trick too," since we also deal with harmful microbes. Thus, humans have extracted these natural antibiotics, turned them into medicines, and have used them to our advantage since.

Why is all this necessary to study?

It is important to study both the beneficial and harmful strains (or versions) of microbes to figure out what makes them the way they are. It's kind of like dating. There are good people and there are bad people, but you don't know which one is which until you study and interact with them.

Over time, you start noticing patterns or certain behaviors that make you go "Nah, you gotta go!" or "Hmm, you just might be the one" That's basically what happens when folks put on their lab coats in microbiology. They are just studying bacterial behavior over time by replicating the conditions they may experience in nature.

When scientists notice "toxic" behaviors in bacteria, they study the chemicals aka antibiotics that other bacteria use to knock down the harmful bacteria. Then, they take these natural antibiotics and find a way to turn them into medicines. After that, the drug goes through clinical trials and must be approved by the government via the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before doctors and nurse practitioners safely prescribe it to people.

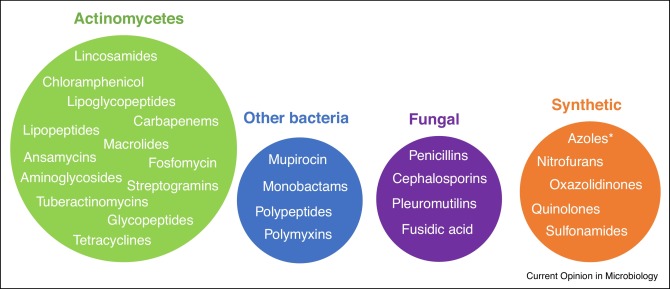

While natural antibiotics are fascinating, they aren't the only kind. There are also synthetic antibiotics, which are entirely man-made, and semi-synthetic antibiotics, which start as natural antibiotics that scientists chemically tweak.

Hutchings' paper explains that the first antimicrobial drug, Salvarsan, was released about 100 years ago. Although it was synthetic rather than a natural antibiotic, it was important because it showed scientists that they could design chemicals to specifically target harmful microbes.

Later, Penicillin, an antibiotic that comes from mold, helped to kick-start the discovery of natural antibiotics. These discoveries later helped scientists understand how to develop cancer drugs, organ transplants, and more. Isn't it amazing how a single discovery can open the doors to so many others? That's the beauty of science; it’s like a domino effect, where one finding sets off a chain reaction of innovation.

What is Antibiotic resistance?

Historically, moldy bread was once used to treat open wounds, and soil was considered medicinal because it contained bacteria that produced natural chemicals that inhibit harmful microbes.

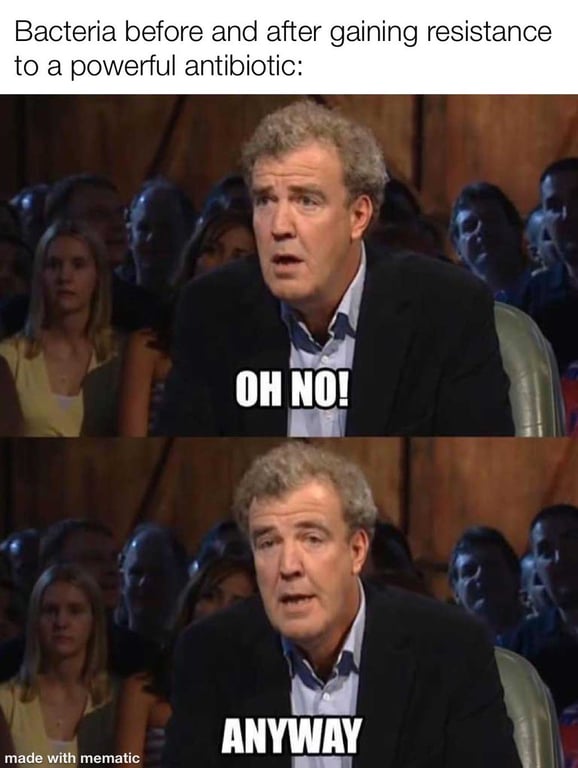

There was a period called the Golden Age of Antibiotic Discovery (1940s- 1960s) when new antibiotics were discovered almost every year. However, discoveries have slowed in recent years because the downside of all this discovery though is that harmful microbes can be very clever.

Over time, they can become antibiotic-resistant, meaning the chemicals that once killed them or stopped their growth no longer work. Think of it like an ex that still finds a way to show up at a family function or that sends emails even after their number is blocked. Similarly, harmful microbes find new ways to escape the chemicals meant to stop them.

Many bacteria that were once affected by antibitoics have become resistant. When doctors tell you to finish the course of your antibiotic treatment, it is not a mere suggestion, but it is to prevent antibiotic resistance, by making sure all the harmful bacteria are eliminated, leaving none behind to adapt and come back stronger.

How do we combat Antibiotic resistance?

In general, antibiotics come from four main sources: Actinomycetes (soil bacteria), other bacteria, fungi, and synthetic compounds, with the ones coming from Actinomycetes clinically dominating. Hutchings explains that governments are trying to find different ways to tackle antibiotic resistance, and some have put their money towards creating more synthetic antibiotics, but these have not been as successful.

In recent years, governments are seeing more value in the natural antibiotics, and realizing there are still so many out there in natural habitats that need to be discovered, specifically the antibiotics that come from bacteria in marine environments.

Many of the natural antibiotics come from soil bacteria called Streptomycetes (a type of Actinomycete), but this is just scratching the surface, so looking at more different kinds of soil can lead to more discovery of natural antibiotics.

What is the main takeaway?

In conclusion, harmful bacteria are constantly evolving, becoming more clever over time, and developing more antibiotic resistance. That's why Hutchings and colleagues emphasize that it is important for scientists to continue to look for more natural antibiotics. Nature still has a lot of untapped potential as it relates to antibiotic discovery. We just have to keep looking!

Thank you for reading. Be on the lookout for the next paper I breakdown!

-Léonella

Léonella © 2025